#but instead of making jokes i just do like. a reverse directors commentary.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

alright look i know my following is not the target audience for this kind of post but i wanna at least point something out about a scene in the Fallout show that i haven't actually heard a single person point out or comment on.

spoilers ahead.

in the scene where the ghoul is rewatching his old movie, specifically the scene where he originally protested about killing the villain.

the first layer is the obvious one: he is talking directly to himself. "you were strong, ugly, and you had dignity. i'll give you two out of those three." he remembers what happened at that shoot just as clearly as we did, and after he literally tells himself to his face "you're strong, ugly, and have no dignity" followed by him killing the man he originally wanted his character to save. this, of course, coming DIRECTLY after the person he sold into slavery earlier that day sparing him with life saving medicine while he's on the ground and telling him to his face that he only lives on because someone stuck to their humanity. very heavy! i bet he feels like shit, which he probably should because he's kind of a jerkoff! (but in a cool way that i like to watch)

the SECOND layer is the one i find way more interesting. the phrasing of his final line we didn't hear before was so dripping with importance that it felt like i was reading RPG dialogue and story relevant words were highlighted. "i hope you like the taste of lead you commie son of a bitch". as we'd already seen in episode 3, he despises vault-tec for everything he knows they are responsible for while he was their face. moreover, it's made clear that he doesn't just resent himself for being used for their image, but he resents the fact that he was the face of the propaganda which drove the war fever that caused the end of the world. the wild west ideal caricature of masculine wisdom from the movies as the spokesperson of the company who stood to profit from the purposeful decimation of the human race. he became The Ultimate Jingo.

and i really enjoyed how brief yet informative that detail was! i really enjoyed how the directors tell you what the characters are thinking intuitively and effectively through the camerawork and those little details make the whole thing a lot more fun to mull over and consider as a part of the whole of Fallout! i think it's neat.

#text#fallout show#im not joking when i say ive considered recording a podcast that's just a rifftrax over the episodes of fallout#but instead of making jokes i just do like. a reverse directors commentary.#i do an audience commentary where i point out what all the shit means and how cool it is

259 notes

·

View notes

Text

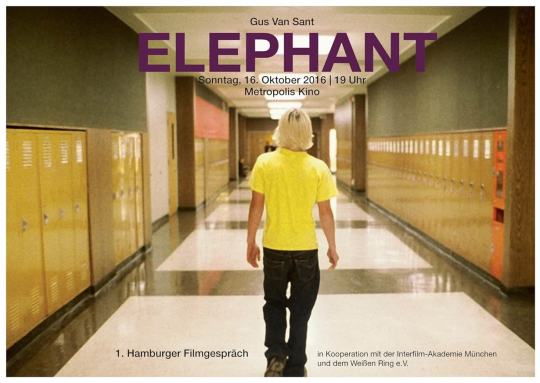

Elephant (2003)

Spoilers for this movie.

Directed and written by Gus Van Sant, Elephant is an hour and a half long film that jumps back and forth between the mornings of several high schoolers, on the day of a school shooting that takes the lives of 13 students. It features Alex Frost and Eric Deulen as the shooters, who are, coincidentally, named Alex and Eric. That's something strange about this movie; most of the cast has the same first name as their character. John Mcfarland is played by John Robinson, Eli is played by Elias McConnell, Jordan Taylor plays Jordan, Carrie Finklea and Nathan Tyson play Carrie and Nathan.

The movie was made only a few years after the Columbine High School tragedy, and was clearly based off it, down to scenes like students being shot in the library or the principal's death.

Watching this film was one of the tensest experiences I've had. We learn that a shooting will happen fairly early and are forced to watch these characters carry out their day and lives, knowing we can only witness what will happen next. What's worse, we never know when the shooting is coming.

We also bear witness to many signs that the boys will be committing this act very soon. Alex is bullied and lonely in school, but this movie manages to portray him in a way that does not make us sympathize with him. While we see what he sees, we are not forced to sit through a bullshit excuse for what he did.

Him and Eric enjoy playing violent video games together, although I admit that's a stupid theory people blame shootings on. They purchase guns on the internet, which stunned me, as I had no idea you could just do so.

Then, there's a slightly conflicting scene, of Alex and Eric implied to be having sex before they shoot up the school. When I first watched it, I believed the two were supposed to be gay, and the film was making some very worrying statements about why 'gay people are dangerous.' But no, upon a rewatch of the scene, they state clearly that it's because neither of them have had sex yet, and they wanted to before they died.

The movie actually includes some refreshing queer commentary, from director/writer Van Sant, who is a gay man. My personal favorite is a scene of a student attending a gay-straight alliance meeting.

The GSA scene is one continuous 360 degree shot of each member's face, as they, including the teacher, discuss topics like 'if a man wears pink and rainbow, is he gay?' and if homosexuality is reversible, according to an article about 'gay rams' reared by farmers. This scene was both impressively shot and scripted, not to mention an amazing portrayal of how most school-issued queer spaces, like the GSA, are a complete joke.

Overall, it's a film made to show people how devastating and traumatic these incidents are, and truly humanizes the victims instead of the shooters, when the news media was doing the complete opposite and sensationalizing the Columbine shootings. As a film, I've heard many call it boring, but I didn't feel that at all. The movie is certainly a painful watch, but a great experience that leaves you feeling changed. I give it a 7.3/10 and I recommend it.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Venn diagram of least popular sub-genres

Full title: Venn diagram of no one’s gonna click it (but the readers who found me are real gems)

I’m wrapping up my Batman/Some Dude fluffy-kinky-queer romance novel this week, and pondering the things I’ve learned about fandom trends in my endless combing of the metadata. (I’m a librarian and an author craving validation, it’s what I do.) It’s doing phenomenally well within its niche, but oy, the niche.

Disclaimer: I’m not judging anyone’s taste here! You wanna read what you wanna read. (In library nerd: “Every book its reader; every reader their book.”) I’m just a data nerd talking out loud as a record for myself while it’s top-of-mind.

How are people less likely to click on my fic? Let me count the ways:

1. Some Dude: Average general fandom readers and M/M readers (usually myself) aren’t much interested in OC-centric works. There’s a preponderance of canon men to choose from for pairings and a perception that the average quality bar is lower on self-insert writing. (As an aside, I suspect this is just Sturgeon’s Law writ large. The top 1% of 200 fics is 2 great ones. The top 1% of 45k fics is 450 great ones including 45 heartbreaking works of staggering genius, and never dipping down past page 20 to find the also-rans.)

I expected this, and was relieved to get some “I usually don’t even click these, but wow, yours is good!” comments, because it meant my summary/tags were reaching at least a few of the larger audience.

2. Batman: I’m writing a Bruce Wayne-centric fic, which is fundamentally less popular in the AO3 Batman fandom than Robin-centric by an impressive margin. (The exceptions are Superbat or Batjokes, see point 1.) I did not expect this.

3. Some Named Dude: There is a thriving little sub-genre of Canon Character/Reader fic! (News to me!) I was initially excited by this potential readership! Which... overwhelmingly focuses on Female Reader characters and likes them as generic as possible to the point of writing “Y/N” (Your Name) instead of giving the character a name or characteristics.

CC/Reader is the preferred tag; it has substantially more works and more kudos per work than CC/Original Character, even when the content is the same down to calling them Y/N.

Ditto CC/Female or Unspecified vs CC/Male.

So my named male original character with a Very Opinionated Queer Identity and big social activist subplot did not get a lot of pickup from that direction.

Strategies that did work and ways that my readership has made me ever so happy and grateful:

A. I am a metadata monster and was very clear with both findable and interesting tags and summary, so anyone who might be willing to give it a chance at least has an attractive cover to consider.

B. It’s long, it has a lot of chapters, and I had a clockwork 3x week update schedule keeping me on or near the front page for four months. Even though new readership has leveled out, I still get about 2 new Kudos per update, someone commenting for the first time about twice a month, and presumably some silent subscriptions I don’t know about.

C. I reply to all comments in the same level of detail and enthusiasm as the commenter, and use that space to give behind-the-scenes info and jokes, like director’s commentary. People have really responded to this; my measurable fanbase has leveled off, but the ones I’ve hooked are steadfast. I have multiple people who comment almost every chapter and our conversations are GREAT. People have also asked me to have opinions on Tumblr and, hello, yes, thank you, you are wonderful for my ego.

I have more than 3x as many comments as kudos, in a sharp reversal of all possible trends. Not so great for search results and hooking later readers, but seriously. I am currently in the top 0.3% of Batman fics sorted by comments and how is that even real. How do I have over 700 comments? Half of them are mine, but that’s true of many thriving comment sections. Sometimes I just go roll around in them and feel happy like a dragon with a hoard.

My heap of comments is more than enough to make me feel proud of the uptake my fic has gotten. Yes, I’m always greedy for kudos because I’m a filthy author and want to be at the top of the search results, but that number going up is a (delicious) one-time rush. Comments I can chew over and over and feel gleeful that I made that connection with someone.

My fic gets marked Complete this Friday. I know many people don’t commit to reading an epic until they know it’s Done, and many people don’t comment until they finish reading a work, so I’m curious how that will affect my stats. (Maybe a few recs? Fingers crossed.)

There is no punchline. I’m writing in a deeply weird niche. My commenters are amazing and I’m grateful to them. This has been a post. 💚

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

⭐ for either of the Should I Stay (Or Should I Go?) fics!

*rubbing my hands together* [Should I Stay (Or Should I Go?) - ASOUE/Stranger Things AU]

Okay here’s something I’ve been DYING to talk about: picking everyone’s superpowers! I wanted everyone’s abilities to relate to either their personality, plot or special interest, so it took a lot of thought!

Violet’s ferrokinesis was definitely the easiest power to come up with; she’s an inventor, so metal manipulation was an easy jump.

What actually took the longest time to come up with, though, was her Extrasensory Perception- the original plan was for Klaus to be only one with that, as he has the same powers as El and she seems to have ESP, but long story short it got added to Violet’s skillset as a way to solve a plothole I’d written myself into, and with that came the ESP-Klaus, which is probably one of my favorite parts of the AU.

Klaus’s power honestly went back-and-forth between El’s in-show powers (telekinesis, ESP) and the information absorption that was later given to Sunny; while info absorption would work with his book special interest, it was a bit hard to figure out how to work that into his subplots, and when I eventually decided on Quigley’s power being teleportation, I figured someone needed telekinesis in order to close the Gate in S2, so Klaus got the traditional 011 powers.

That was a complete coincidence, btw; the experiments’ numbers were decided on birth order, starting with Jacques and ending with Carmelita [Ellington was added later, Olaf is an exception since he joined the project late, so he could really be any age inbetween Beatrice and Jacques/Kit], and Klaus just so happened to fall into the 011 position while having her powers. [You’ll notice that Kit has the Kali-style illusions, instead of Duncan/008.]

His ESP was originally going to show up in S1, but I couldn’t find a good place to put it, so that ability only appeared in S2.

Both Sunny and Carmelita’s powers were written in as a “their powers have already awakened but nobody’s going to notice because that’s just how they are in canon” twist. Sunny in the books has piranha-teeth and remarkable intelligence for her age, so I just was like “alright that’s her power. super-strength and hyperintelligence.”

The information absorption, honestly, was added in so I could joke about her driving a car (she absorbs info from the manual), and the ESP was basically just my way of making her, as Carmelita called her, the baby-ex-machina. I needed the kids to find specific articles/information within the timeline, so her being able to sense things of importance was a good way to get that done.

Duncan and Isadora’s powers were very easy- I wanted them to have complimentary powers, since they’re basically always together, but also have their powers tie into their special interests, which just made Telepathy and Empathy an obvious choice. Duncan’s journalism is more about facts, which would make mindreading a useful skill (if he ever got over how much he hates violating people’s privacy), and Isadora’s poetry is definitely very emotional.

Duncan’s memory-reading was added in order to give us Rainbow Room flashbacks, and also as a way to make his powers more obvious to him- he could explain away hearing voices, but if he goes into Klaus’s memory, it’s a bit hard to deny something supernatural’s going on.

Isadora’s pathokinesis was mostly given as a way to give her some form of offensive power, also I find the idea of emotion-manipulation very unsettling and badass and wanted to write it in.

Quigley’s power, as I implied in Klaus’s description, was a tossup between telekinesis and teleportation. I needed him to open the Gate, but I wasn’t sure if that necessarily meant he had to have El’s powers; besides, teleportation was a bit more related to his cartography special interest.

Eventually I came up with the idea of the Gate opening due to his teleportation powers going off the rails, so the telekinesis went to Klaus.

His powers honestly got more figured out as S2 went on; as he got stronger, he got more abilities, such as the ability to transport more than one person. If he practices enough, he might be able to escape handcuffs or teleport to specific people instead of places by S3, though that all depends on what the plot calls for.

Should also mention that his teleport to Hawkins in S2 was a mixture of him desperately wanting to go somewhere safe (IE with his siblings) and the Mind Flayer wanting him in Hawkins as a spy.

Fiona’s story honestly changed drastically from the original concept- she was originally much closer to El than Kali. The first draft idea had her as another experiment who’d never been outside the Lab, who Violet would befriend whenever they were in the Rainbow Room and promise to help, and her power was some form of plant manipulation (IE mushrooms), though I wasn’t entirely attached to the idea at all; I wasn’t sure how I’d be able to write her into the plot convincingly, or how to keep her plant powers from being OP (think Layla in Sky High).

Her change was actually @asoue-sideblog‘s idea; while I was pitching the AU to her and mentioned I wasn’t entirely sure about Fiona’s power, she suggested poison manipulation (IE Medusoid Mycelium), and from what I remember, her ending up more as a Kali-figure just snowballed from there.

She does have weaknesses, though; she has to know what poison she’s manipulating, and if she uses too little, she runs the risk of someone realizing what’s happening and escaping before they can die. If she uses too much, she loses energy, as seen at the end of S1 when she’s starting to black out in the Lab.

As mentioned with Sunny, Carmelita’s ability was made to be so close to her original characterization that nobody would notice. (though a few of you guys did pick up on the implications of her wearing a million slap bracelets on her arm!) Everyone in the books always listened to her, so that got into the SIS AU in the form of her persuasion powers, which were also used to get her out of the Lab and into the Spy position.

I tampered with a few ideas for extra powers, but eventually decided to (at this point) leave it as is; she doesn’t really need offensive powers when she can just talk her opponents down.

(this is getting kinda long so adults under the cut, includes spoilers both for the fic itself and for ATWQ)

ask for the “director’s commentary” on a particular story, section of a story, or set of lines, or, send in a ⭐star⭐ to have the author select a section they’ve been dying to talk about!

Ellington, as mentioned, was added very late; once I decided that Armstrong Feint was going to be in charge of the project, I figured it’d make sense to have her as an experiment, but the problem was I’d already run out of numbers. So she’d have to have an excuse to not be tattooed, and her shapeshifting arose both from that and from Ellington Feint’s disguises (as Cleo and Filene respectively). The giveaway of her green eyes is because they were mentioned so much in ATWQ that it made sense to have them be important here.

I had plans for her and Lemony to appear in S2, but couldn’t figure out how to work them into the plot, so they’ll be saved for S3-4.

Jacques’s power wasn’t explained too much in S2, as it wasn’t incredibly important to the plot and he’s already dead by this point, but he basically just has extreme extrasensory perception; much more than the Baudelaires, and enough that he could sort-of project himself into other places to see what was going on.

Him being able to enter the Void was added as a way to get Violet to learn that ability via Kit.

Kit’s power was up in the air for a while, and unfortunately she was plot-relevant so I couldn’t just be vague about it. @asoue-sideblog can confirm that we tampered with the idea of just giving her Renesmee’s powers from Twilight until I was just like “wait we could just give her illusions. works with her lowkey shadiness and the fact she’s basically just reverse!Kali.”

Olaf’s power also took a while to decide, and I had him has having power-absorption for a while until I realized “huh that’d leave a lot of plotholes in the story, like why he couldn’t just absorb some of Violet’s ferrokinesis and do the tests himself when she was refusing to.” Him having Clairvoyance ties in a bit to him constantly finding the Baudelaires in canon and always seeming to have a plan, and it not being an offensive power would explain why Violet/Quigley never saw it; you’d think he’d use an offensive power at the very least to intimidate, if not injure.

Lemony’s psychometry was also suggested by @asoue-sideblog and I love because it works perfectly with his canon investigative interests; he can discover literally anything he wants just by touching the right object.

He gained more control over his power as he got older, though he still gets overstimulated at times (something him and Duncan would be able to bond over, I’m sure), meaning he can just channel into himself what information he wants instead of all the information there is, as well as control when the power is on or off.

And finally, Beatrice’s pyrokinesis was one of the first powers I decided, though I did occasionally consider giving that power to Olaf instead. So much of canon is tied to fire, especially including the fact the Baudelaire Fire kicks off the plot, so it made sense that someone would be pyrokinetic, and who better than Beatrice, who’s so woven into the fabric of ASOUE that it’s impossible to tell the story without her, even if she doesn’t appear onscreen? (*cough*movie*cough*)

Of course, she does appear onscreen in SIS, multiple times; it would’ve been hard to do otherwise, as the plot begins with Violet’s abduction, and I wanted to establish the Baudelaire family bond before her kidnapping. Writing her and Bertrand was a bit of a challenge, cause they had to be established as good parents who love their children, but who are also keeping an incredibly deadly secret from them.

The burns on her hands, permanent from her trying to summon some flames before she awakened her fire immunity, were mainly added as an excuse as to why she’s wearing gloves, one that Violet and Klaus wouldn’t question, so they wouldn’t realize she was 003 until it was too late. She also does have a few weaknesses in her power; as was seen in SIS, she can’t control smoke, meaning that smoke inhalation is still a threat to her even if the flames aren’t (I like to think that her magic fire doesn’t have smoke, though, so this would only be a problem with actual fire), and what I have written as a weakness for her that never got mentioned in the fic is that she has trouble summoning fire in cold temperatures.

Should also mention that I do have powers planned for Friday, if I can write in a way for her to show up w/ powers, and I have some ideas for Bea II, who I think you’ve figured out is definitely going to appear. But I’m not going to mention them here, because…

ask for the “director’s commentary” on a particular story, section of a story, or set of lines, or, send in a ⭐star⭐ to have the author select a section they’ve been dying to talk about!

#asoue#asoue netflix#a series of unfortunate events#stranger things#should i stay au#mine#ask#anonymous#fanfic director's cut

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Best Films of 2019, Part IV

Part III, Part II, Part I PRETTY PRETTY GOOD MOVIES

62. Shazam! (David F. Sandberg)- One of the most comic-booky movies to come around in a while in the sense that it seems to be in fast forward for the first third, using shorthands because it has too much story to tell. I am sad to report that Shazam! has no Movie Stars in it, and I didn't realize how essential those were to the superhero genre. There is a cagey standalone quality to its modest bets though. I like that it's anchored in a real place and isn't afraid to be a little too scary for kids. I would see it mostly as a product of potential though, for a funny Jack Dylan Grazer, for the filmmakers, and for the studio. As a student of weird billing, I have so many questions about Adam Brody getting awarded fifth lead for a bit part.

61. Fighting with My Family (Stephen Merchant)- Dwayne Johnson as producer feels like the auteur here, since the formulaic story has more to do with his combed-over, please-everyone persona than with Stephen Merchant's more messy, improvisatory style. I couldn't care less about the time spent on Jack Lowden's brother character, but I was impressed with the physical part of Florence Pugh's performance. This is a movie you've seen a hundred times, but it hits most of its marks skillfully. 60. Spider-Man: Far From Home (Jon Watts)- This is a movie in which a spurned tech innovator uses drone projectors to stage a battle in which he defeats an elemental water monster to save Venice. The best sequence is one in which a boy tries to trick his friends into letting him sit next to the girl he likes on a flight. 59. John Wick: Chapter 3- Parabellum (Chad Stahelski)- What a criticism it is to claim that the filmmakers give in too much to fanservice, especially since I don't know what that word means anymore if something like this is the monoculture. So they gave us, the audience, what we wanted, and I was upset that it was two hours and ten minutes? Seriously though, have you ever eaten too much ice cream? 58. Fyre (Chris Smith)- An interesting yarn that gets at the foolishness of Internet influencing better than anything else that I've seen. I was surprised by how distant many of the subjects seemed, as if only the Big Bad Billy was responsible for any misleading. And I was grateful that, despite the level of criminality on display, it was still as funny as the tweets were at the time. The film lacks shape though, and it would be nice to have somebody smart on hand to answer questions. Can someone explain to me why it's so important that the island used to be Pablo Escobar's? Why should I want to be like Pablo Escobar? 57. Leaving Neverland (Dan Reed)- Part 1 works because of the striking similarities in the parallel stories, as well as the subjects' perspicacious understanding of their own emotions and childhood psychology. So Part 2 gets extremely frustrating when these men, who have already proven how articulate they are, seem puzzled by the obvious psychological problems they have as adults. 56. Diane (Kent Jones)- This movie is kind of good when it's purely slice-of-life, before it declares what it is. It's very good once it declares itself as a routine of self-flagellation, a sort of Raging Bull for women with multiple recipes for tater tot hotdish. It's a little less good when it speeds up and goes back on that thesis near the end. For the record, I think Mary Kay Place is fine. I don't get the critical adoration.

55. Rocketman (Dexter Fletcher)- If the choice is Bohemian Rhapsody or this, then I'll take this every time. Unlike the former, Elton John's life doesn't present an obvious high point in the second half or easy conflict for the first half. As a result, the relationships within John's family seem broad with manufactured conflict. (His birth father's hardness isn't that far off from Walk Hard's "wrong kid died.") But there's an authenticity here that's refreshing, a respect to the unique friendship between Elton and Bernie and a respect for the transformative power of the music. That sincerity extends to Egerton's generous performance, which nails the self-effacing Elton John smile. So there are some biopic structural problems that can't be helped, but if only to admire the '80s fits that Elton gets off, attention must be paid. 54. Triple Frontier (J.C. Chandor)- A useful example for differentiating between tropes and cliches of the action drama genre. For someone who gets less amped than I do for dudes meeting in a shipping container to have a conversation about how "now is the time to get out," it's probably full of cliches. For fans of hyper-masculine parables about getting a team together (that are also sort of meta-commentaries on their lead actor's fallen star), it's full of tropes. 53. The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part (Mike Mitchell)- The plot is nearly incoherent, and the sequel isn't really satirizing anything like the first one was. But the jokes come at a Zucker-Abrahams-Zucker clip. A character in a car chase saying, "It's like she knows my every move" before a cut reveals he's been using turn signals? That's some Frank Drebin stuff. 52. Long Shot (Jonathan Levine)- Jonathan Levine has carved out an interesting directorial space for himself, with a career far different from what I imagined when I saw and loved The Wackness, a film to which I'm a little afraid to return. Levine is making, at the highest level possible ($40 million budget?), the types of movies that we claim don't get made anymore. A one-crazy-night Christmas comedy, an adventure comedy, and now a political romantic comedy, all with top flight Movie Stars. Long Shot seems like a rare opportunity to put Seth Rogen and Charlize Theron together and do something special, and what we come out with is...cute. For every good decision the film makes--what a supporting cast, all playing rounded characters--it makes a bad one--leaning too heavily into Rogen's patented "I don't really know what we're yelling about" delivery. The music is uninspired, but the presidential satire is pretty clever. The rhythm of the film is jagged and doesn't really cut together, but the script is very fair to the Theron character. Even in the general tone of the film's politics, it declares a few ideals, but those positions are still too neutral and obvious. I had a good time, but in a more capable director's hands, this experience wouldn't feel like math. 51. Isn’t It Romantic (Todd Strauss-Schulson)- So frothy that it almost doesn't believe in itself, especially near the end, but I found myself laughing a lot. Regarding the gay best friend, I'm very interested in the space of politically incorrect humor that is acceptable only because the work has built up self-awareness in other areas. That's a difficult negotiation, but this movie balances it. 50. Yesterday (Danny Boyle)- There's one twist that stretches the moral center of the film, and two minutes later there's a twist that's probably just a bridge too far in good taste. Other than that, this is a really cute Richard Curtis script, and it's nice to hear "Hey Jude" on movie speakers. 49. Ready or Not (Radio Silence)- Short and spicy, despite one or two too many twists. I'm in the front row of the Adam Brody Revival, but I appreciated the movie more as an exercise in the paranoid misery built into wealth. I wish I could have written the line down, but Alex says something like, "I didn't realize how much you could do just because your family said that it was okay," and that's the whole film. If you can, see it without watching the trailer first.

48. The Laundromat (Steven Soderbergh)- Mary Ann Bernard is a Steven Soderbergh pseudonym, but what if he did hire an outside editor? What if someone saved him from himself? It's hard to believe that Meryl Streep is the heart of the film--if the film's thesis is "The meek will inherit the Earth?"--if we go on a twenty-minute detour to an African family and a ten-minute detour to China. I laughed quite a bit, and I admire the audacity of the ending. But this is a movie that knows what it's about without knowing how to be about it.

47. High Flying Bird (Steven Soderbergh)- As a person who can cite most NBA players' cap figures off the top of my head, I should love High Flying Bird, a movie about a sports agent who tries to topple the system during an NBA lockout. Instead I liked it okay. It takes an hour to kick into high gear, but once it does, some self-contained scenes are powerhouses, and the writer of Moonlight was always going to provide an emotional kick that is sometimes absent from Soderbergh's work. Like Soderbergh's Unsane from last year, High Flying Bird is shot on an iPhone, an appropriate form given that the execution is a do-it-yourself parable that takes place mostly inside. Soderbergh is a man who has always tried to trade the ossified system of moviemaking for experimentation, so most reviews have pointed toward the meta quality of capturing a character doing that same thing in another medium. Like most of his post-retirement work, however, I find myself asking one question: "Would anyone care if this were made by another director?" 46. Piercing (Nicolas Pesce)- Good sick fun with a taste for the theatrical. I saw twist one and twist three coming, but twist two was ingenious. It ends the only way it can, which is okay. 45. Booksmart (Olivia Wilde)- At first the film is hard to acclimate to, stylized as it is into a very specific but absurd setting, counteracted by a very specific and realistic relationship. The music cues are all awful until the Perfume Genius one, which is so perfect that it erases the half-dozen clunkers.But it's smartly funny, funnily warm, and warmly smart. The screenplay does some clever things with swapping the protagonists' wants and needs at crucial times. Molly will have an obvious drive that overrides Amy's fear, and then a few scenes later, there will be an organic reversal. 44. Joker (Todd Phillips)- Joker presents more ideas than it cogently lands. I don't disagree with Amanda Dobbins's burn that it feels more like a vision board than a coherent story. Still, its success kind of fascinates me. This dark provocation, shot on real locations, has way more in common with Phoenix entries like You Were Never Really Here than it does with the DCEU. In fact, the comic book shoehorns feel like intrusions into a story about a guy who likes to Jame Gumb skinny-dance. Dunk on me if you want, but I think it's most eerie and affecting as a portrait of mental illness. Whereas Joker is a criminal mastermind in Batman lore, this is a guy helpless enough to scrawl into a notebook, "The worst part about having a mental illness is pretending to people that you don't." And that idea gets borne out in a scene in which he's pausing and rewinding a tape to study how a talk show guest sits and waves like a regular person. It's rare enough to see a person this mentally ill depicted on screen; it's even rarer to see someone this aware of his own isolation and otherness.

0 notes

Text

Link’s Awakening and the Reverse-Engineering Nature of Parodies

March 13, 2020 11:00 AM EST

The off-beat and tongue-in-cheek nature of The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening may actually make it one of the purest Zelda experiences.

When observing with a long-running and venerable series such as The Legend of Zelda, it isn’t difficult to see how it becomes slavish to a formula that has slowly developed over time. For that reason, entries like Majora’s Mask and Breath of the Wild instantly stand out for their incongruent and formula-breaking nature. Yet one of the more unusual and off-kilter entries in the Zelda canon is The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening, a game that was developed with that very formula in mind.

Link’s Awakening contains all of the usual puzzles, dungeons, and explorations that classic Zelda games have, but features cameos from characters expatriated from other Nintendo franchises such as Mario and Kirby. Koholint Island, where Link is stranded, is a Twin Peaks-inspired place both wonderful and strange, featuring a cast of oddball supporting characters and bizarre labyrinths.

When speaking about the production and conception of Link’s Awakening, developers and producers often called the game a “parody” of Zelda games, which led me to ask a fundamental question: what exactly does a parody entail?

There was an era in popular culture in which whenever the word “parody” arose in conversation, the first piece of media that would be recalled was Scary Movie, and the bastardized Jason Friedberg and Aaron Seltzer-helmed follow-ups like Epic Movie, Meet the Spartans, and Vampires Suck—nothing more than crude and sophomoric reference-fests. Those wiser to the history of the cinematic genre of parody would instead hearken back to the works of Mel Brooks or Zucker, Abrahams and Zucker, the latter team responsible for Airplane! and The Naked Gun trilogy.

Little explanation is needed for why disaster film parody Airplane! is an exemplary comedic film, but I found myself extracting a greater deal of humor once I started working backward from the film’s point of origin. The 1980 film is nearly a word-for-word remake of the 1957 straight disaster film Zero Hour!, with Airplane! peppering in a number of verbal and visual gags to mock the heightened melodrama and the dire stakes often seen in those usual disaster movies. It became a perfect parody not by pointing out the absurdities, but by inhabiting its tropes and amplifying them for comedic purposes.

Parodies in visual media are not so much for pure mockery and cheap gags; they are meant to highlight tropes and leverage our familiarity with them for comedy. They can bring light to elements of the original source material and inspiration; it’s why the producers of James Bond had a hard time returning to the series after Austin Powers successfully dissected the formula of those films. Other times, it can lead to inspired creative decisions: directors Anthony and Joe Russo, then known for their pointed genre parodies on Community, i.e. the action parody episode “A Fistful of Paintballs,” would successfully reverse-engineer their knowledge of the genre to create the straight action film Captain America: The Winter Soldier.

So who better to parody the Zelda series than Nintendo themselves?

“Self-parody” would probably be the more apt descriptor for Link’s Awakening, but even still, it might be best to use the term loosely. The “parody” elements didn’t come so much from the conceptualization of the game—the developers might say that there wasn’t much of a conceptualization process in the first place, with the off-beat nature of the game coming from a more free form development workflow. Director Takashi Tezuka would say in a 2009 edition of Iwata Asks:

Tezuka: … We moved along at quite a good speed in a relatively freewheeling manner. Maybe that’s why we had so much fun making it. It was like we were making a parody of Zelda.

Iwata: A parody of your own game? (laughs)

Tezuka: Yeah. (laughs)

Iwata: Today, if you just barged ahead using characters resembling Mario and Luigi—even if it were for a Nintendo game—it would be quite a problem.

Indeed, seeing Goombas and Shy Guys and fake Kirbys roaming the overworld of a Zelda title was enough to signal to players that something unusual was afoot. At its core, the story premise of Link’s Awakening is that he is a stranger in a strange land, and having characters that blatantly do not belong in the familiar world of Zelda is a near-fourth-wall-breaking wink to the player for the strangeness to fully register to them—Link’s Awakening depends on the player’s familiarity with Zelda and plays with those preconceptions to drive the weirdness home.

And those pseudo-crossovers are far from the only elements needed to convey this strangeness. As someone who has digested a fair amount of Zelda in the past several years, I found myself amused by some of the methods Link’s Awakening used to guide and give hints to players through my playthrough of the Switch remake. I guffawed the first time I received a hint through a telephone, a completely out-of-place modern device in a high fantasy world.

Puzzles in the Zelda series are usually complex with some vague clues laid about, so imagine my joy when one key puzzle was simply an open area with signposts that very simply and explicitly shouted: “GO THIS WAY” with an arrow pointed in a direction. And then there are the four children in the village, each giving Link button prompts and directions in typical Zelda NPC fashion, while also demonstrating an unusual amount of sentience by following with a variation of the dialogue: “Don’t ask me what that means, I’m just a kid!” Not the most groundbreaking self-aware joke, but let’s say that this was probably good enough for a video game in the early 1990s.

That being said, I would love to see what game developers and writers could come up with in making a modern-day video game that is designed as a parody from its conception. You can say that a handful have tried and failed— the most prolific example might be Eat Lead: The Return of Matt Hazard, a 2009 third-person shooter that attempted to be a meta fourth-wall-breaking parody of games like Max Payne and Metal Gear Solid, making not-so-subtle jokes about in-game glitches, instructional text, tutorial missions, and characters that vaguely resembled Mario, Master Chief, and others. And then you see games like Duke Nukem Forever and the Borderlands series, lazily inserting “remember this?” references through brief dialogue or environmental decoration without having any commentary on their targets.

While Link’s Awakening may not be a straight parody of Zelda, the devil may care attitude towards development led to a lot of moments that poked at brains trained to the standard Zelda conventions and created a unique experience out of it. With Link’s Awakening as a starting point, I yearn for more comedic games that deconstruct and reverse-engineer some of our favorite games and move past silly winks and nudges for cheap, unearned, lukewarm chuckles. Video gaming may be a younger medium than film, the latter being much more susceptible to parody, but in the decades since the original Link’s Awakening, game developers and enthusiasts are familiar enough with the tropes to have a large enough palette to create comedy with.

And as for the Legend of Zelda series, I would hope that the Link’s Awakening remake has had enough people revisit the material for them to realize that this unusual game has a special place in the series. If anyone wants to play the “definitive” and “purest” Zelda game, the fairly obvious choices would be something along the lines of Ocarina of Time, A Link to the Past, or perhaps just the original The Legend of Zelda. But out of all of the games in the franchise, no other Zelda title “gets” Zelda more than Link’s Awakening.

March 13, 2020 11:00 AM EST

from EnterGamingXP https://entergamingxp.com/2020/03/links-awakening-and-the-reverse-engineering-nature-of-parodies/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=links-awakening-and-the-reverse-engineering-nature-of-parodies

0 notes

Text

To Boldly Go

When the great film trilogies are listed, the back-to-back run of Wrath of Khan, The Search for Spock and The Voyage Home are rarely mentioned. For starters any franchise from the 1980s, where roman numerals were thrown about merrily, will bear suspicion of artistic scepticism. Indeed, it wasn’t until JJ Abrams’ reboot that the idea would even be considered that any film from this franchise might be taken seriously as a piece of cinema rather than a routine trip for Paramount to milk their cash cow. Star Trek was considered niche entertainment for nerds with occasional nostalgic crossover appeal; something to be acknowledged as popular to a degree but rarely held up as anything like the best of what the medium has to offer. In these three films, however, there can be found huge creativity, bold authorial choices, and a keen sense of storytelling momentum based around a compelling and hugely resonant central theme. Within the genre, the films could hardly be more different from each other: Wrath of Khan is a peerless adventure, blending themes of obsession and revenge with adventure and duty, heavily inspired by the swashbuckling tales of 18th century naval adventures. The Voyage Home, on the other hand, is a prime example of the 1980s fish-out-of-water comedy subgenre. Bridging them is the film considered the least of the three but, whilst it is perhaps the most conservative in terms of scale, the propensity for The Search for Spock to be dismissed as “an odd numbered one” masks the moments where it comprehensively masters what the entire franchise was all about. With its operatic brio and earnest embrace of famous science fiction tropes, director Leonard Nimoy’s The Search for Spock is an underrated film in an underrated trilogy and, 35 years on, hiding within it is a 20-minute sequence which, for this writer, remains the defining moment within the entire franchise.

Within the film it is quickly established that the crew have a chance to do right by their fallen comrade, but have been ordered in no uncertain terms to keep away from his resting place. For Kirk, permission is not a luxury he has ever particularly sought and, from the moment he growls “The word is no: I am therefore going anyway”, the film releases the melancholy of its mournful opening act. Sporting a magnificently implausible leather collar, not enough is made of just how good Shatner is in these films. His impudent charisma led us to genuine heartbreak in the previous chapter and he sustains Kirk’s unimpeachable authority with effortless ease. We can see our hero struggling, failing, learning but never yielding, but to see his plan through he needs his crew, leading to why the scene that follows soars: it is the definitive instance of the Enterprise crew working as one. The dramatic stakes are unusually low in this film: there is no universe to save this time, just one man. The gentle inversion of Spock’s “needs of the many” axiom is honest and maybe a little unsubtle but certainly compelling, and a theme throughout the film of what we do for those who matter the most to us is precisely what elevates this franchise above its peers. Those who dismiss Star Trek as frivolous miss this central pull: each crew is always based around this core camaraderie, an ensemble of characters whose loyalty inspires. The Search for Spock is dramatically least compelling of the trilogy but emotionally the most resonant.

The crew plot to steal back their battered starship in what becomes, atypically for the franchise, a set piece. This segment has the feel of a caper to it and eschews visual fireworks for a steady and patient escalation of the stakes and an intensifying focus on the faces of the actors to build the drama: we know what this crew is risking here and we become desperate for them to succeed. On paper what follows is simply some light levels of banter, a few sweaty brows and the Enterprise reversing out of a garage and yet it is imbued with such an epic scale for these characters that it swells the heart. The heist itself has a giddy sense of fun to it, of propulsive excitement: composer James Horner uses an eclectic percussive string instrument (a cimbalom) to set this feeling, but it builds slowly and steadily. The choice to gradually intensify the scope throughout a longer set piece was not out of character for the time and, one suspects, borne from budgetary restrictions, but certainly it would be unimaginable to find such patience in a modern blockbuster, and even the most recent and honest tribute Star Trek Beyond overflows with startling visuals during its own action beats.

The pace of the escape is determined in part by the choices made by previous directors Robert Wise and Nicholas Meyer, as Trek had already decided that, instead of the buzzing, kinetic spitfire battles of the Star Wars films, these ships of the line would be enormous stately galleons. Harder to manoeuvre, they add an epic scale to even the smallest of lines: “One quarter impulse power” is followed soon after by an “Aye Sir”: this is, after all, the finest crew in the fleet. There are other advantages as ILM’s gorgeous models have aged exceptionally well, bringing a physicality that later CGI struggles to recapture, whilst the elegant iconography of the famous ship is amplified by Nimoy’s of framing it from differing scales.

As the heist develops it allows the crew to quietly shine. Long reconciled to be left supporting the core leads from the side-lines, Nimoy recognised that the whole film would greatly benefit from using his castmates to add shading around the edges, and he spends snippets of time on the Enterprise crew, implying in his director commentary that he had to defend this choice, one assumes, to Shatner. Whilst Kirk remains his old gung-ho self (only a single punch of a security guard is needed) Nimoy gives Sulu, donning what appears to be a cape, a moment of nonchalant badassery, notably showing us Kirk’s reaction of impressed surprise. The message is simple- nobody messes with our heroes and McCoy repeats this to Uhura in a similarly authoritative beat moments later. The caper crackles with its own history and our heroes (and the script) are visibly enjoying themselves here: McCoy’s smile as his friends break him from his jail is magical, whilst the dialogue is peppered with jokes and callbacks to the Kobayashi Maru, or Spock’s revenge on McCoy “for all those arguments he lost”. The final flourish is the addition of an antagonist: the film sets up the USS Excelsior as a new and improved Federation prototype (an idea which is immediately offensive) and their priggish, pompous captain is instantly hissable. Nimoy knew better than anyone that TV sets were awash with talented actors who had more depth to be exploited, casting Taxi’s Christopher Lloyd as his villain and using Hillstreet Blues actor James Sikking here. Sikking does an incredible job with a small part, immediately making Captain Styles a startlingly slappable presence. After being bruisingly insensitive to Scotty (writer Harve Bennet’s lists Scotty’s reply as his favourite line in the film), when we see Styles aboard his titanic ship he is blithely filing his nails and taking a no-look grab of what appears to be a redundant space cane. Styles is not the only example of how the storytelling detail and colour in this section, with a janitor looking on agog as the Enterprise makes her exit, building a sense of scale, opportunistic adventure and disbelief that Kirk, the Federation’s greatest hero, was going rogue. Styles’ final decision, calling out Kirk (by name, not rank) gives the scene’s final punchline a pleasing rush of schadenfreude.

The final ingredient to this section cannot be overestimated as James Horner’s score develops cues from his Wrath of Khan score (namely Battle in Mutara Nebula & Genesis Countdown- two of the finest cues in 20th century film composition) to lend colossal weight to the enormity of these actions for our heroes. A 91-piece orchestra escalates his two primary themes to a gloriously triumphant conclusion, as Horner deploys the French horns blasting at the limits of their range, a joyous trademark of that composer and an enormous final flourish as the Enterprise finally clears her docks.

Throughout this short set piece, we see Star Trek in a perfect microcosm. Everything that it remains most loved for is perfectly conveyed in this sequence by the script, the direction, the performances, the editing and the composition via an emotional core of considerable heft. When Kirk smiles to say “May the wind be at our backs” and Alexander Courage’s famous fanfare salutes them back, the loyalty and camaraderie of this family is cemented.

It ends as Kirk takes his Captain’s chair; unwavering, resolute and with his crew at his back as the bridge lighting shifts, purposefully.

“Aye Sir.

Warp Speed.”

0 notes

Text

The Emoji Movie

The simplest questions are often the most profound. In the immortal words of the Bard, brevity is the soul of wit, and from this thing's conception to release one short, enduring question was on the tongues of those who followed its development with abject disbelief and those who left theatres with ashen faces and mortified minds.

Why?

Why, in another hapless bid to recreate the wonder of Toy Story while ignoring the heart and soul and messages that Pixar put into their work, did a gaggle of clueless executives greenlight a film about banal emoticons? Why did renowned, veteran, thespian actors agree to be associated with this tripe? Why is this, in all likelihood, still scheduled to make back every bit of the $50 million that went into funding this misadventure?

All these and countless more burning queries raced through my mind as I watched the procession of images flash before my disbelieving eyes. I left bamboozled, befuddled, discombobulated, uncertain as to whether or not what I witnessed was some crazed fever dream that would make Hunter S Thompson blush with admiration. But alas, my faculties were intact, and on sitting down to write this I am reminded once more that this is a product that was indeed released to the public. Such is the world we live in today.

Above everything else, this is a product. It is not something made with creativity in mind, nor is it a bold, intrepid venture into unexplored territory. This is a bold-faced, utterly unabashed advertisement for apps wearing the guise of a family feature, born from a desire to exploit new "toys", and the film's "plot", for lack of a better word, is likewise slapdash. It's a generic, tepid "be yourself" story interspersed with blatant product placement so shameless that Mac and Me finds itself humbled. Gene, a phone-dwelling "meh" emoticon in a society where emojis can only perform the task they're given or display the emotion they're assigned, is played flatly by TJ Miller who gives a performance that never rises above passable – something shared across virtually every single performance in the film. He stumbles from app to app, paying dues to rapacious corporations and blundering through sessions of Candy Crush and Just Dance as he tries to change his abnormally expressive ways through enlisting the assistance of a hacker named Jailbreak, played by Anna Faris who may or may not have been reminiscing about her Scary Movie glory days in the recording booth.

Throughout this arduous and asinine voyage, barring one brief yet merciful stretch, they are accompanied by one of the most ruthlessly humorless comedic "sidekicks" in recent cinematic history, a disturbingly uncanny hand frozen into a high-five inventively called Hi-5 who is left bitter about being laid by the wayside and denied the digital high life he once indulged in. They're pursued by Smiler (Maya Rudolph), the perpetually grinning, gratingly-voiced overseer of the city of Textopolis – and the film's idea men pat each other on the back vigorously – who seeks to eliminate Gene due to the threat he poses to the system as a "malfunction". All the while, the phone's teenaged owner, high school freshman Alex, is grappling with what many monied first-world children in the world today struggle with: smartphones. And a romantic crush. But mostly smartphones.

So our bumbling band of bozos go, off on a merry adventure towards discovery and self-acceptance so obviously telegraphed that it's safe to say you could watch it with your eyes clamped shut. Off a minuscule 86-minute running time, even less factoring in the credits, the film catapults itself through the motions and inserts every single cliche that it can crowbar into the script. Emotional moments are glanced over, striking changes are reversed in only a handful of scenes, everything feels like it's on fast-forward and consequently the central cast remains only slightly less threadbare than when they started out on their grand odyssey. It's a ceaseless barrage of noise, light and sound, with barely any downtime to allow the audience to breathe and digest, and nothing sinks in as a result. But even with this in mind – surely, if the visuals and pacing are troubled, an outstanding script can make up for such shortcomings.

Maybe so, but certainly not here. Instead, courtesy of writer-director James Leondis and fellow collaborators Eric Siegel and Mike White – whose presence is nothing less than utterly perplexing considering his repertoire – we get such insightful, thought-provoking rise on subjects like the personal desires and the changes in the way people communicate as "Wow, that's a super-cool emoji!", or "What's the point in being number one if there aren't any other numbers?" The entire script reeks of unabashed sloth. Modern lingo is crudely shoved into conversations because it is modern, ergo funny, ergo guaranteed money in the eyes of executives without any need of context or effort. In a thoroughly galling display, it shamelessly pilfers dialogue from timeless classics in a desperate bid to please any older or more cinephilic viewers who have the misfortune of watching it. Lyrics from popular songs are outright lifted to serve as plot points, and amid such platitudes almost every single statement that masquerades as a "joke" is painfully inept and made as obvious as possible for the sake of the viewers, as if the film takes a perverse glee in belittling the intelligence of the audience it's aimed it. Kids are developing – but they aren't stupid.

Character development is accelerated to ludicrous speed on all fronts as the movie barrels through the beats in a desperate attempt to end faster, and Gene is the only member of the cast who comes even remotely close to possessing some kind of arc. Hi-5 is almost completely devoid of anything resembling a character, and James Corden's proven comic chops are non-existent as the character exists chiefly to bombard the audience with insipid zingers. Jailbreak, aside from being the token female love interest and action girl, is similarly unrealised and bounces around aimlessly. Her reasons to exist alternate haphazardly; sometimes she is there to spout oddly-inserted feminist tracts about alleged emoji sexism and ignored female ingenuity, make forced statements on girl power and use random slang to appeal to the trendy crowd – "Slay!" she cheerfully shouts at one point for no discernible reason, after being invited by Gene to "put some sauce on that dance burrito" – and sometimes she's an average tough chick doing hacker business or bantering, or preaching the wonders of youness. Steven Wright and Jennifer Coolidge provide perhaps the only truly noteworthy performances in the film as Gene's parents, Mel and Mary Meh, whose attitudes are strikingly reflective of what the average moviegoer feels when bearing witness to this drivel.

Everything from the story to the characterisation to the humour falls utterly flat and summarily this is a blunder, a mess in every sense of the word. The lone high points are one or two genuinely amusing quips that seem positively restrained compared to the rest of the script, and the visual presentation of the digital realm that is distantly evocative of the mindscapes of Inside Out, steeped in corporate avarice instead of encapsulating developing emotions. Leondis, an avid fan of Pixar's work, tries to recreate its splendor but it is something that is simply out of his grasp. Pixar's creations are founded upon a bedrock of passion and there is precious little in the way of passion to be found here – this is not someone's baby. It is the spawn of a think tank, made solely to leech off of that which is popular, rake in a guaranteed profit and get people in seats. It is filmmaking at its most hollow, little more than extended lip service to financial benefactors while having only the barest of necessities for any kind of three-act structure, and it's a painful experience that ultimately overwhelms the few faint glimmers of hope the film has.

But it's not panful merely because of its narrative deficiencies, or crude and obvious humour, or even the nature of its existence. Above all else, the most painful aspect of this misguided endeavor is that there was promise. In a culture so thoroughly addicted to smartphones and so enamoured with all things digital as our own, a film that anthropomorphises emojis and bandies them about as the hot new way to communicate and calls them the pinnacle of technological innovation – "Words aren't cool", a friend of Alex's glibly opines near the film's beginning – this entire concept could have served as some lighthearted yet rather timely and incisive social commentary. Everywhere we look, people are glued to their phones, and there are fleeting glimpses of the possibilities that this film had that are buried away, chiefly manifesting in the real-world segments. Alex, his crush Addie and his friends are consistently enraptured by the technology they possess. For them, the world rests comfortably in their pocket, almost every interaction they make is done wirelessly, and even in the realm of the emojis the film offers some sparse commentary on the subject as Gene and his companions briefly advertise Facebook - they interact with people they don't even know, all for the sake of achieving popularity. With the right amount of self-awareness and an analytical outlook mixed into its script, it could have at least attempted to deliver on the promise that its premise held. It could have been something else, something worth thinking about, a cautionary tale on the direction our society is going in thanks to these miniature worlds within worlds, these do-all creations and enduring distractions no bigger than the palms of our hands. But honestly, the moment Sir Patrick Stewart was cast as a walking, talking mound of excreta, I believe this film's fate was sealed long before it even hit the screens.

If there is any consolation to be gleaned from this experience, however, I can report that the screening I attended was as silent as a crypt. Perhaps the developers aimed wide and went for all the wrong wisecracks – or, maybe, the youth of today have grown wise to the soulless pandering that the film industry so frequently churns out. As a firm believer in the potency of human intelligence and ingenuity, I reside firmly in the latter camp.

0 notes